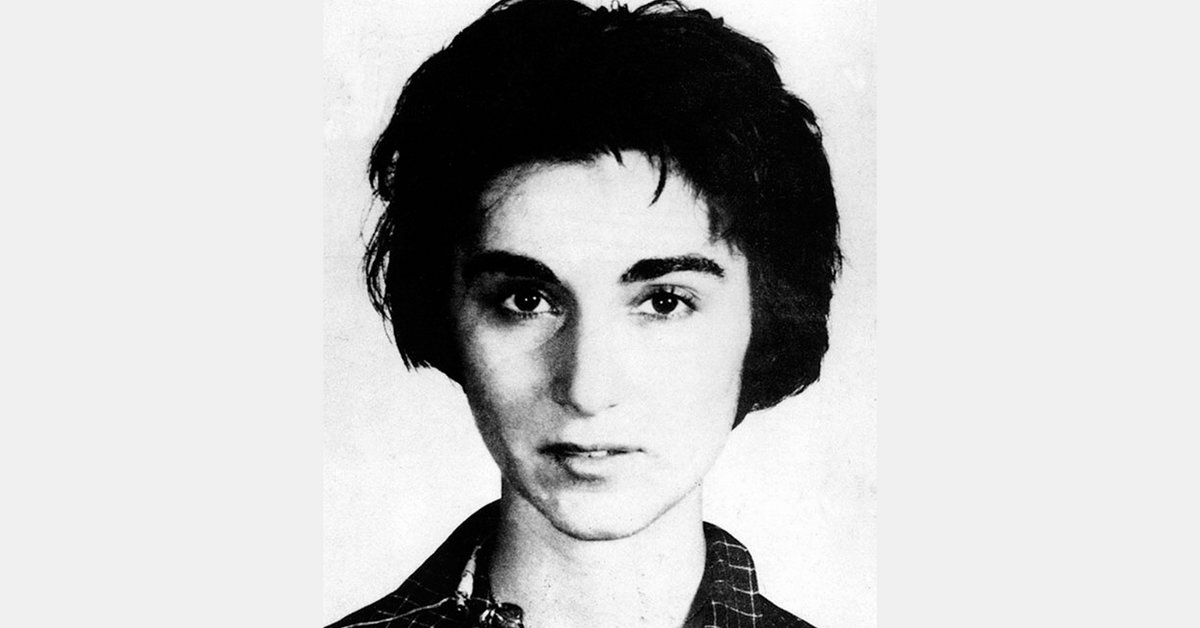

Kitty Genovese’s murder has inspired psychological research, publications, songs, and television shows. A few days after the murder, on March 27, 1964, The New York Times published an article in which people saw and did not call the police. A discussion began about the soullessness of the inhabitants of big cities. This was blamed, for example, on television showing violent films. Kitty’s death becomes a story about the apathy of society.

Kitty was the eldest of five children in an Italian-American family. I worked as a bar manager. On March 13, 1964, she returned home as usual after work. Once Winston Mosley, armed with a knife, ran up to her near her apartment. I screamed for help and managed to run away. Perhaps due to her injuries, she was no longer able to scream out loud. The killer got into his car and drove away. Then he came back ten minutes later. He found a semi-unconscious Genovese at her door, stabbed her again, raped her, and fled.

Initial police contact reports were vague and said the woman was beaten but got up on her own. The investigation revealed that many witnesses had heard or seen parts of the attack, but no one was aware of its full trajectory. Most people testified that they thought it was the sounds of a family argument, but the cries of a woman defending herself against an attacker.

Kitty Genovese’s killer was arrested two weeks later during a robbery. He was a married man with three children. He confessed to the Genovese murder, two sexual murders, and multiple robberies. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. He died at the age of 81 in a maximum security prison

Witnesses to the crime considered the event to be a quarrel between a man and a woman due to the influence of social stereotypes. This worried psychologists in the 1960s, who began looking for an answer to the question: why so many people who witnessed the murder did not react. They find a connection. The more witnesses to a crisis event are on the scene, the less likely someone is to react appropriately to it. Bystanders are less likely to help the victim if other people are around. The more likely someone is to intervene. These facts today are known to everyone, then they were a discovery.

The irony is that the New York Times text that provoked psychologists to make these discoveries turned out to be incorrect. In fact, only two people saw the murder – one screamed at the attacker, the other – and alerted the ambulance and the police. The description, made up for a larger drama, was corrected by the editors only in the mid-1990s.

Created Date: Today 12:31

Echo Richards embodies a personality that is a delightful contradiction: a humble musicaholic who never brags about her expansive knowledge of both classic and contemporary tunes. Infuriatingly modest, one would never know from a mere conversation how deeply entrenched she is in the world of music. This passion seamlessly translates into her problem-solving skills, with Echo often drawing inspiration from melodies and rhythms. A voracious reader, she dives deep into literature, using stories to influence her own hardcore writing. Her spirited advocacy for alcohol isn’t about mere indulgence, but about celebrating life’s poignant moments.